- Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, constipation)

- Heart-rate increases (dose-dependent)

- Hypersensitivity reactions (rash/itch/urticaria)

- Discontinuations & severity (mild–moderate predominance)

- Serious adverse events & deaths (trial reports)

- Other GI monitored (diarrhoea, reflux, dyspepsia)

- Hepatic/biliary & pancreatitis (monitored endpoints)

- Injection-site reactions (monitored)

- Summary of side effects

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Understanding the retatrutide side effects is essential for anyone considering this next-generation weight loss and diabetes therapy. Clinical trials have shown that retatrutide, a triple-agonist targeting GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors, offers powerful metabolic benefits, but like all medications, it comes with a defined safety profile. On this page we break down the evidence from studies so far, looking at common tolerability issues such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation, as well as other monitored risks including heart rate changes, hypersensitivity, and pancreatitis. Each section is based on published trial data, giving you a clear, balanced view of what rare side effects have been observed to date.

Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, constipation)

One of the most consistent findings across the clinical development programme for retatrutide is the presence of gastrointestinal (GI) side effects. These events are well recognised with incretin-based therapies such as GLP-1 receptor agonists, and retatrutide has shown a similar pattern in the early studies. The most common GI issues reported so far are nausea, vomiting, and constipation.

These symptoms generally appear during the first few weeks of treatment, particularly during dose escalation phases when the body is adjusting to the drug. Although they can be unpleasant, they have typically been described as mild to moderate in intensity rather than severe. In the phase 2 obesity and diabetes trials, more participants receiving retatrutide reported nausea compared with those in the placebo group.

Vomiting was also more frequent among treated patients, but again, the majority of cases were considered mild and did not require hospitalisation or additional medical treatment. Constipation was another commonly noted event, reflecting changes in gut motility that are associated with this class of drugs.

Importantly, diarrhoea, which is often a side effect with similar treatments, did not show a significant increase compared with placebo in the published analyses. This suggests that Retatrutide’s GI profile is somewhat more focused on nausea and constipation rather than the broader range of digestive disturbances. Trial investigators paid close attention to the timing and pattern of these side effects.

Ready to Order?

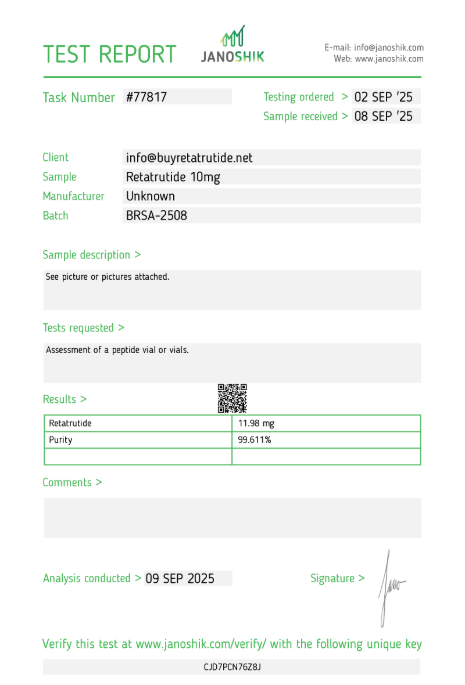

Choose your preferred amount below, fast shipping and secure checkout.

-

Reta 10mg 3 Vials

£195.00Independently verified COA. UK stock, worldwide delivery. For lab use only.

Data indicate that nausea and vomiting usually occur early, sometimes within the first few doses. For many participants, these symptoms improved after the body adjusted, especially when the dose was increased gradually. This process is known as titration, and it helps the gut adapt to the hormonal changes triggered by the medication.

Constipation, by contrast, tended to persist for longer in some individuals, but it was generally manageable with diet, hydration, or standard remedies. The use of gradual titration schedules has therefore been a key part of trial protocols and is expected to remain central if retatrutide reaches routine clinical use.

When looking at the overall impact on trial participation, gastrointestinal issues were rarely a reason for discontinuation. While some participants did stop treatment because of nausea or related symptoms, the overall discontinuation rates for retatrutide were not substantially higher than those for placebo.

This is an important point because it suggests that most people who experience these side effects are able to continue therapy, especially with appropriate support from healthcare teams. Many patients also reported that the intensity of nausea or vomiting lessened after the initial adjustment period, making the treatment more tolerable over the longer term.

From a safety perspective, the gastrointestinal side effects of retatrutide have been viewed as expected, dose-related, and manageable. They align closely with what is already known about GLP-1 receptor agonists and similar multi-agonist peptides.

What makes retatrutide stand out is the apparent dose-dependence: higher doses were linked to a greater likelihood of nausea and vomiting, while lower starting doses were associated with a gentler side effect profile. This has guided the strategy of beginning at a lower dose and stepping up slowly, which mirrors the approach used for other drugs in the same family, such as semaglutide and Tirzepatide.

Overall, gastrointestinal side effects remain the most prominent tolerability issue for retatrutide. They are not usually dangerous and do not appear to carry long-term consequences, but they can affect quality of life in the short term and may discourage some patients from staying on therapy without careful management.

For those considering or prescribed retatrutide in the future, it will be important to receive clear guidance on how to manage nausea, maintain hydration, adjust dietary habits, and use dose escalation schedules to minimise the discomfort.

Based on trial evidence so far, the majority of participants find these side effects tolerable and temporary, allowing them to continue with treatment and benefit from the drug’s effects on weight loss and metabolic health.

Heart-rate increases (dose-dependent)

One of the more carefully observed effects of retatrutide in clinical studies has been its impact on resting heart rate. This is a class effect that has been documented with GLP-1 receptor agonists and other incretin-based drugs, and researchers wanted to know whether retatrutide followed a similar pattern.

The evidence from phase 2 obesity and diabetes trials suggests that it does, although the magnitude and time course of the effect is becoming clearer as more data are published. In the largest phase 2 obesity trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, investigators reported a dose-dependent rise in resting heart rate.

In other words, participants who received higher doses of retatrutide tended to see bigger increases, while those on lower doses saw only modest changes. The pattern was fairly consistent across dose groups: the heart rate increase began in the early weeks of therapy, peaked around week 24, and then showed signs of gradual decline towards baseline as the trial continued.

This trajectory suggests that the body may adapt over time, although not all participants returned to their exact baseline values by the end of the study period. The average magnitude of heart rate rise was reported to be in the range of a few beats per minute, with higher-dose arms experiencing the larger end of that spectrum.

For example, while placebo participants remained essentially unchanged, those on the highest experimental doses of retatrutide recorded mean increases that were noticeable but still generally below the thresholds considered dangerous in cardiology. Nevertheless, any drug that elevates heart rate attracts careful scrutiny, since persistent tachycardia can, in theory, put strain on the cardiovascular system.

Importantly, the clinical significance of these heart rate rises remains uncertain. To date, there has been no clear evidence of an associated increase in cardiovascular events in the relatively short phase 2 studies. The trials did not report higher rates of arrhythmia, heart failure, or other acute cardiac problems in retatrutide groups compared with placebo.

Longer and larger phase 3 studies will be essential to confirm whether these heart rate changes translate into any tangible risk or whether they are simply benign physiological adjustments to the drug’s mechanism of action. Researchers have speculated about the possible reasons for this effect.

One theory is that Retatrutide’s stimulation of GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors may interact with the autonomic nervous system, shifting the balance towards slightly increased sympathetic activity. Another is that weight loss itself, particularly rapid weight loss, may transiently alter cardiovascular parameters.

As the heart adapts to a lighter body mass and improved metabolic state, small changes in resting rate may be a natural accompaniment. Whether the observed rise is a direct pharmacological effect, an indirect result of metabolic change, or a combination of both remains a subject of ongoing investigation.

For clinicians and patients, the key point is that heart rate increases were observed, but they were generally modest, dose-related, and appeared to lessen over time. Participants did not report subjective symptoms such as palpitations or chest discomfort at a higher frequency than placebo, and discontinuations due to heart rate were not a major feature of the trials.

Nevertheless, this is an effect that will continue to be monitored closely in phase 3 programmes, especially in populations with underlying cardiovascular disease. In summary, retatrutide is associated with transient, dose-dependent rises in resting heart rate. These effects have so far been small in magnitude, without clear evidence of harm, and they appear to diminish after about six months of treatment.

Ongoing research will clarify whether these changes have any long-term consequences or whether they are simply part of the expected pharmacological profile of this new class of therapy.

Hypersensitivity reactions (rash, pruritus, urticaria)

Alongside gastrointestinal issues, another category of side effects that has been observed with retatrutide in the clinical development programme is hypersensitivity reactions. These events were tracked closely in trials because peptide-based medicines, including GLP-1 receptor agonists, have occasionally been linked to allergic responses ranging from mild skin irritation to more pronounced immune-mediated reactions.

In the published data to date, hypersensitivity with retatrutide has mainly taken the form of non-severe skin conditions such as rash, itching (pruritus), and urticaria (hives). In pooled analyses of randomised controlled trials, participants treated with retatrutide experienced a higher frequency of hypersensitivity events compared with placebo.

The absolute numbers were small, but the signal was consistent enough to be reported across different dose groups. Most cases were described as mild and self-limiting, meaning that they either resolved without treatment or improved with basic measures such as antihistamines or topical creams. Importantly, no cases of anaphylaxis or other life-threatening allergic reactions have been reported in the trial literature so far.

The presentation of hypersensitivity was typically dermatological. Patients reported redness, small patches of rash, or generalised itching, usually developing within days to weeks of starting the medication. In some instances, urticaria appeared as raised, itchy welts on the skin.

These episodes tended to be sporadic rather than continuous, and most resolved within a short timeframe. Only a minority of participants chose to discontinue treatment because of hypersensitivity, and discontinuation rates for these reactions were not significantly higher than those observed with placebo groups. Trial investigators emphasised that these reactions were non-serious and manageable.

Standard allergy management advice was sufficient in nearly all cases, and no long-term consequences have been documented. As with many drugs that involve repeated injections, distinguishing between injection-site reactions and true systemic hypersensitivity can be challenging.

However, the analyses specifically separated out skin irritation confined to the injection area (such as redness or swelling at the injection site) from more generalised immune-type reactions such as rash or hives affecting distant parts of the body. From a mechanistic perspective, hypersensitivity with retatrutide may reflect the immune system reacting to a synthetic peptide sequence, a phenomenon not unique to this drug.

GLP-1 receptor agonists and similar incretin-based therapies have occasionally shown the same profile. Because these reactions were predictable, mild, and reversible, they have not raised major safety concerns in the regulatory discussions to date. Nevertheless, ongoing surveillance in larger and longer phase 3 trials will be crucial to confirm that no rare but serious allergic patterns emerge as more patients are exposed.

For patients and prescribers, the practical takeaway is clear: hypersensitivity reactions can occur, but they are usually minor. Anyone starting on retatrutide should be made aware of the possibility of rash, itching, or hives, and should be advised to report any new or worsening skin symptoms promptly.

Healthcare professionals are expected to manage these events with standard antihistamine therapy if needed, and only rarely would discontinuation be necessary. At this stage, there is no evidence of severe allergic outcomes, which is reassuring for both clinicians and patients. In summary, retatrutide has shown a slightly increased risk of mild hypersensitivity reactions compared with placebo.

These have been non-serious, manageable, and have not resulted in significant discontinuation or safety concerns. As clinical research continues, this area will remain under close watch, but the data so far suggest that allergic responses are limited in severity and do not pose a major barrier to treatment.

Discontinuations & severity (mild–moderate predominance)

When assessing any new medicine, it is not only the number and type of side effects that matter, but also their severity and impact on treatment continuation. In the clinical trials of retatrutide conducted so far, one of the key observations has been that while side effects were relatively common, they were overwhelmingly mild to moderate in intensity.

This pattern is consistent with what has been seen for other GLP-1 receptor agonists and related incretin-based therapies. Investigators reported that the majority of adverse events did not lead to participants stopping treatment. Gastrointestinal issues such as nausea and constipation were the most frequent complaints, but in most cases they improved over time or were manageable with standard supportive care.

As a result, the discontinuation rates attributed directly to side effects were relatively low and, importantly, were not substantially higher than those recorded in the placebo groups. A pooled analysis of early-phase studies found that treatment discontinuations due to adverse events were rare. Even when side effects were present, most participants continued in the trial, suggesting that the tolerability profile is acceptable.

This is a critical finding because high dropout rates can undermine the usefulness of a treatment in the real world. For retatrutide, the balance appears favourable: participants were generally willing to tolerate the expected side effects in order to remain on therapy and benefit from its strong weight-loss and metabolic outcomes. Severity grading in the trials followed standard regulatory frameworks.

Mild events were those that caused some discomfort but did not interfere with daily activities, while moderate events might have limited activity but did not require hospitalisation. Severe events, defined as those substantially interfering with function or requiring medical intervention, were very uncommon.

In most reports, fewer than a handful of severe side effects were documented across treatment groups, and there was no significant imbalance compared with placebo arms. It is also important to note that the titration schedule used in trials was designed specifically to minimise tolerability problems.

By starting at a lower dose and increasing gradually, investigators reduced the burden of side effects and kept discontinuation rates low. This strategy has been highlighted in publications as one of the key reasons why trial completion rates were high despite the expected GI issues and other tolerability signals.

From a practical perspective, this means that if retatrutide is eventually approved for use in obesity and diabetes, most patients can expect side effects to be manageable and temporary. Clinicians will likely follow the same pattern of gradual dose escalation to help patients adjust.

Based on current evidence, only a small proportion of people will need to stop treatment due to tolerability concerns, and the overwhelming majority of reported side effects will fall into the mild-to-moderate category. In summary, discontinuations due to side effects with retatrutide have been infrequent, and the vast majority of adverse events reported so far have been mild or moderate in nature.

This is reassuring for both clinicians and patients, as it suggests that although side effects are expected, they rarely force people to abandon treatment. The tolerability profile therefore compares favourably with other agents in the same therapeutic class.

Discontinuations & severity (mild–moderate predominance)

When assessing any new medicine, it is not only the number and type of side effects that matter, but also their severity and impact on treatment continuation. In the clinical trials of retatrutide conducted so far, one of the key observations has been that while side effects were relatively common, they were overwhelmingly mild to moderate in intensity.

This pattern is consistent with what has been seen for other GLP-1 receptor agonists and related incretin-based therapies. Investigators reported that the majority of adverse events did not lead to participants stopping treatment. Gastrointestinal issues such as nausea and constipation were the most frequent complaints, but in most cases they improved over time or were manageable with standard supportive care.

As a result, the discontinuation rates attributed directly to side effects were relatively low and, importantly, were not substantially higher than those recorded in the placebo groups. A pooled analysis of early-phase studies found that treatment discontinuations due to adverse events were rare. Even when side effects were present, most participants continued in the trial, suggesting that the tolerability profile is acceptable.

This is a critical finding because high dropout rates can undermine the usefulness of a treatment in the real world. For retatrutide, the balance appears favourable: participants were generally willing to tolerate the expected side effects in order to remain on therapy and benefit from its strong weight-loss and metabolic outcomes. Severity grading in the trials followed standard regulatory frameworks.

Mild events were those that caused some discomfort but did not interfere with daily activities, while moderate events might have limited activity but did not require hospitalisation. Severe events, defined as those substantially interfering with function or requiring medical intervention, were very uncommon.

In most reports, fewer than a handful of severe side effects were documented across treatment groups, and there was no significant imbalance compared with placebo arms. It is also important to note that the titration schedule used in trials was designed specifically to minimise tolerability problems.

By starting at a lower dose and increasing gradually, investigators reduced the burden of side effects and kept discontinuation rates low. This strategy has been highlighted in publications as one of the key reasons why trial completion rates were high despite the expected GI issues and other tolerability signals.

From a practical perspective, this means that if retatrutide is eventually approved for use in obesity and diabetes, most patients can expect side effects to be manageable and temporary. Clinicians will likely follow the same pattern of gradual dose escalation to help patients adjust.

Based on current evidence, only a small proportion of people will need to stop treatment due to tolerability concerns, and the overwhelming majority of reported side effects will fall into the mild-to-moderate category. In summary, discontinuations due to side effects with retatrutide have been infrequent, and the vast majority of adverse events reported so far have been mild or moderate in nature.

This is reassuring for both clinicians and patients, as it suggests that although side effects are expected, they rarely force people to abandon treatment. The tolerability profile therefore compares favourably with other agents in the same therapeutic class.

Serious adverse events & deaths (trial reports)

One of the most important safety considerations in any clinical programme is the potential for serious adverse events (SAEs) and, ultimately, any deaths that occur during treatment. For retatrutide, all reported SAEs have been carefully scrutinised in both phase 2 obesity studies and diabetes-focused trials.

The findings so far are encouraging: while adverse events are common, the serious end of the spectrum has been relatively rare, and there have been no signals of increased mortality associated with the drug. In pooled analyses of randomised controlled trials, researchers found that the overall incidence of SAEs in retatrutide groups was not significantly higher than in placebo groups.

This means that although serious health problems did occur among participants, they were not more frequent in those taking the drug compared to those who received an inactive injection. This is an essential distinction because clinical trial participants often have other underlying health conditions, and some serious health events are expected in any large study population regardless of treatment.

The specific SAEs that were documented included events such as gastrointestinal complications, infections, and cardiovascular-related issues. However, these events occurred at a low frequency, and none appeared to be driven by retatrutide itself.

For example, pancreatitis and gallbladder-related problems are closely monitored in all incretin-based drug trials, but so far, retatrutide has not been associated with a statistically significant increase in these conditions compared with placebo arms. Similarly, no increased signal of arrhythmia, heart failure, or major cardiovascular events has emerged in the data published to date.

The phase 2 obesity trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported a small number of SAEs across both active and placebo groups. Importantly, there were no deaths attributed to retatrutide.

A dedicated sub study in patients with type 2 diabetes, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, confirmed this picture: gastrointestinal side effects were the most common adverse events, but no deaths were reported during the trial period. Regulatory guidance requires that all deaths and serious health events be documented, whether or not they are thought to be related to the study drug.

So far, deaths that have occurred during retatrutide trials have been assessed and found to be unrelated to treatment. They were attributed instead to background illnesses or conditions that would be expected in the study populations, such as cardiovascular disease or other chronic health issues. The context matters here.

Retatrutide is being studied in individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes, populations that already carry higher risks of cardiovascular events, liver disease, and other serious conditions. The fact that SAEs in the retatrutide groups have not exceeded those in the placebo groups is reassuring.

Still, researchers emphasise that longer phase 3 studies with larger populations will be required to fully rule out any rare risks that might not show up in smaller trials. In summary, current evidence indicates that retatrutide has not been linked to an excess of serious adverse events or deaths compared with placebo.

While careful monitoring continues, the safety profile at the serious-event level appears consistent with other drugs in the GLP-1 class and does not present unexpected risks. This conclusion will continue to be tested as phase 3 programmes progress, but for now, the data suggest that Retatrutide’s most notable safety issues remain on the tolerability side rather than in life-threatening outcomes.

Other GI monitored (diarrhoea, reflux, dyspepsia)

Beyond nausea, vomiting, and constipation, the clinical trials of retatrutide also monitored a range of other gastrointestinal (GI) side effects. These included diarrhoea, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and dyspepsia (indigestion).

Such outcomes were assessed systematically in all phase 2 studies because they are known to be potential concerns with incretin-based medicines and can affect both tolerability and patient satisfaction with treatment. Interestingly, the pooled trial data showed that diarrhoea was not significantly increased in retatrutide-treated groups compared with placebo.

This finding is somewhat different from the experience with other GLP-1 receptor agonists, many of which report diarrhoea as a common side effect. While some participants on retatrutide did experience loose stools or increased bowel frequency, the rates were broadly comparable with those seen in control arms. This suggests that Retatrutide’s GI tolerability profile may lean more toward constipation and nausea than towards diarrhoea.

Reflux symptoms, such as heartburn or acid regurgitation, were tracked as part of the safety monitoring. In the published analyses, rates of reflux were low and did not show a significant difference between treatment and placebo groups. When symptoms did occur, they were almost always mild and managed with over-the-counter remedies such as antacids.

Importantly, there were no signals of severe oesophageal complications or cases requiring withdrawal from treatment. This is a positive finding, as reflux can be a troublesome side effect for some patients and could otherwise undermine compliance. Dyspepsia, or indigestion, was also reported in a small proportion of participants.

Symptoms included bloating, discomfort in the upper abdomen, and feelings of fullness after eating. Like reflux, dyspepsia did not appear at significantly higher rates in retatrutide groups compared with placebo. When it was noted, it tended to overlap with the early treatment period and was often transient.

Patients reported that symptoms generally improved as they adapted to the medication and as the titration phase progressed. From a clinical perspective, the fact that these secondary GI effects were mild, infrequent, and not statistically elevated over placebo is reassuring.

It suggests that while some patients may notice indigestion, occasional heartburn, or bowel changes, these are unlikely to be dominant features of the drug’s tolerability profile. By contrast, nausea, vomiting, and constipation remain the more predictable GI concerns that clinicians will need to manage proactively.

Trial investigators emphasised that supportive care strategies – including dietary adjustments, hydration, and use of standard medications – were sufficient to manage these milder GI issues. None of the trials reported a meaningful impact on discontinuation rates due to diarrhoea, reflux, or dyspepsia.

This contrasts with the experience of nausea, which although still manageable, was the more common reason for dose interruptions or early withdrawal. In summary, while diarrhoea, reflux, and dyspepsia were monitored carefully in retatrutide studies, the data so far indicate that they are not major problems. These side effects occurred at low rates, were usually mild, and did not force participants to abandon treatment.

For patients, this means that while digestive changes are possible, the biggest challenges with retatrutide remain nausea and constipation rather than these secondary GI complaints.

Hepatic/biliary & pancreatitis (monitored endpoints)

Because retatrutide targets multiple metabolic pathways, its effects on the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas have been a priority in clinical safety monitoring. Incretin-based drugs as a class have previously raised questions about the risk of pancreatitis and gallbladder-related disease, so all retatrutide trials to date have tracked these outcomes closely.

To this point, the evidence has been reassuring: pooled analyses show no statistically significant increase in pancreatitis or hepatobiliary events compared with placebo. In the phase 2 obesity trial reported in the New England Journal of Medicine, pancreatitis was monitored as a pre-specified safety endpoint.

Across all dose groups, only a very small number of cases were reported, and the rate was not higher in the retatrutide arms than in the placebo arm. Similar findings have been noted in diabetes-focused sub studies, where participants are already at elevated baseline risk for pancreatitis due to metabolic disease. No consistent signal has yet emerged to suggest that retatrutide increases this risk.

Gallbladder and biliary complications have also been an area of interest. Drugs that cause significant weight loss can sometimes be associated with gallstone formation or biliary colic. In retatrutide studies, these events were rare and occurred at comparable rates between active treatment and placebo.

A handful of cases of cholelithiasis (gallstones) and cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation) were reported, but none were considered drug-related by investigators. Instead, they were attributed to background risk factors common in obese populations, such as rapid weight reduction and metabolic comorbidities. The liver safety profile of retatrutide has so far been favourable.

Liver enzyme tests, including ALT and AST, were monitored throughout the trials. No significant elevations attributable to the drug were observed. In fact, improvements in metabolic parameters such as insulin sensitivity and body weight are thought to have beneficial downstream effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is common among patients with obesity and diabetes.

Although these improvements were not the primary endpoint of the studies, they are considered an encouraging secondary observation. From a mechanistic point of view, concerns about pancreatitis and hepatobiliary disease stem from the way incretin-based drugs alter digestion and bile flow. However, the current trial data with retatrutide suggest that these theoretical risks have not translated into clinical problems.

Monitoring will continue in phase 3 trials with much larger populations, which will be essential to detect any rare but serious events that smaller studies cannot reliably capture. For patients and clinicians, the practical message is reassuring: retatrutide has not been associated with increased risk of pancreatitis or liver injury in studies so far, and gallbladder events appear rare and manageable.

Those beginning therapy may still be monitored with routine liver function tests and advised to report abdominal pain promptly, but there is currently no indication that retatrutide carries a high risk in these domains. In summary, the available data suggest that Retatrutide’s effect on hepatic, biliary, and pancreatic safety endpoints has been neutral.

Pancreatitis and gallbladder events have not been elevated compared with placebo, and liver enzymes have remained stable. As with all emerging therapies, longer and larger studies will provide a fuller picture, but at present there is no evidence of serious hepatic or pancreatic harm linked to this drug.

Injection-site reactions (monitored)

Like many modern peptide-based therapies, retatrutide is delivered by subcutaneous injection. This naturally raises the possibility of injection-site reactions, which are a well-known class effect with GLP-1 receptor agonists and related incretin-based drugs.

During the phase 2 trials, researchers monitored injection-site tolerability closely to ensure that local reactions did not undermine patient adherence or signal broader immune-related problems. The findings to date have been reassuring. Injection-site reactions were uncommon, generally mild, and self-limiting.

The most frequently reported local issues included redness, slight swelling, or itching at the point of injection. These symptoms typically developed within the first day of dosing and resolved within a few days without any need for medical intervention. Importantly, rates of injection-site reactions were not significantly higher in retatrutide groups compared with placebo.

A small number of participants did experience transient skin irritation or mild discomfort at the injection site, but discontinuations due to these reactions were extremely rare. In almost every case, the local reaction was mild enough that treatment could continue without interruption.

This finding aligns with the experience from other GLP-1 and dual-agonist drugs, where local injection issues are acknowledged but rarely present a major barrier to long-term use. It is worth noting that injection-site reactions need to be distinguished from systemic hypersensitivity events.

While both involve the skin, the latter manifests as rash, hives, or generalised itching across multiple body areas, whereas injection-site reactions are confined to the area where the drug is administered.

Clinical trial reports for retatrutide clearly separated these categories, which helps confirm that the observed local events were simply a mechanical or minor immune response to the injection process rather than an allergic reaction to the drug itself. The tolerability of injections is a practical concern for patients considering a therapy like retatrutide.

In surveys and trial follow-ups, participants generally reported that the injections were easy to administer and that the local side effects, when they did occur, were minor compared with the benefits of weight loss and improved metabolic control. No cases of severe injection-site necrosis, abscess, or infection were documented, and there was no evidence of cumulative worsening with repeated doses over time.

From a patient care perspective, the standard advice applies: rotate injection sites, allow alcohol swabs to dry fully before injection, and avoid injecting into irritated or scarred skin. These simple steps can help minimise the risk of local irritation. Clinicians also typically reassure patients that a small amount of redness or itching is common and not a cause for alarm.

In summary, injection-site reactions with retatrutide have been infrequent, mild, and not clinically significant. They did not occur more often than placebo, they rarely affected adherence, and they did not lead to serious complications. For patients, this means that while a small degree of local irritation is possible, injection-site reactions are unlikely to pose any meaningful barrier to treatment.

Summary of Retatrutide Side Effects

Taken together, the available clinical data suggest that Retatrutide side effects are generally manageable and predictable. Gastrointestinal events like nausea, constipation, and vomiting are the most frequent, but they tend to improve with gradual dose titration.

Heart rate increases, hypersensitivity reactions, and mild injection-site issues have been observed, though usually without serious consequences. Importantly, no significant rise in pancreatitis, liver injury, gallbladder complications, or deaths has been detected compared with placebo.

While ongoing phase 3 trials will continue to refine our understanding, the current evidence indicates that most side effects are mild to moderate, short-lived, and do not prevent the majority of patients from continuing treatment. Below we answer some of the most common questions patients ask about Retatrutide’s safety profile.

Order Retatrutide Online

Available in 10mg vials. Select your pack size and checkout securely below.

-

Reta 10mg 3 Vials

£195.00Independently verified COA. UK stock, worldwide delivery. For lab use only.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the most common side effects of Retatrutide?

The most common side effects reported in clinical trials are gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting, and constipation. These are typically mild to moderate in severity.

Does Retatrutide increase heart rate?

Yes, a modest dose-dependent rise in resting heart rate has been observed, peaking around week 24 before trending back down. No serious cardiovascular events have been linked so far.

Can retatrutide cause allergic reactions?

Some participants experienced mild hypersensitivity such as rash, itching, or hives. These were generally non-serious and self-limiting.

How often do people stop treatment due to side effects?

Discontinuation rates due to side effects have been low. Most adverse events were mild or moderate, and dropout rates were similar to placebo.

Has retatrutide been linked to serious adverse events?

No increase in serious adverse events or deaths has been observed compared with placebo in published trials.

Does retatrutide cause diarrhoea?

Unlike some other GLP-1 receptor agonists, diarrhoea has not been significantly increased with retatrutide. Nausea and constipation are more common.

Is pancreatitis a concern with Retatrutide?

So far, no elevated risk of pancreatitis has been found compared with placebo. Monitoring continues in larger phase 3 trials.

Are there liver or gallbladder risks?

A small number of gallbladder events were reported, but rates were similar to placebo. Liver enzyme levels remained stable across studies.

Do patients experience injection-site reactions?

Some mild redness, swelling, or itching may occur at the injection site, but these events were uncommon and not more frequent than placebo.

How can side effects be managed?

Gradual dose titration, hydration, dietary adjustments, and simple remedies like antihistamines or antacids have helped participants manage symptoms effectively.

Compare Side Effect Profiles

Similar GI Side Effects

Different Side Effect Profiles

- Orlistat – GI effects from fat malabsorption

- Phentermine – Stimulant side effects

- Jardiance – UTI risks

View all 48 compound safety comparisons