Introduction to Retatrutide Dosage

On this page we summarise retatrutide dosage exactly as studied in clinical trials, focusing on once weekly dosing and stepwise escalation used to improve tolerability. In published phase 2 studies, participants received subcutaneous injections at fixed weekly intervals with predefined dose levels and gradual up titration schedules rather than ad-hoc adjustments. These data form the basis for the sections that follow on starting dose, titration, and maintenance.

Important: Retatrutide remains an investigational agent and is not approved for human therapy. Any product discussed on this site is supplied for laboratory research only not for human consumption and not medical advice. Our descriptions mirror trial protocols (weekly injections with planned escalation) to keep this guide factual and consistent with the literature.

Ready to Order?

Choose your preferred amount below, fast shipping and secure checkout.

-

Reta 10mg 3 Vials

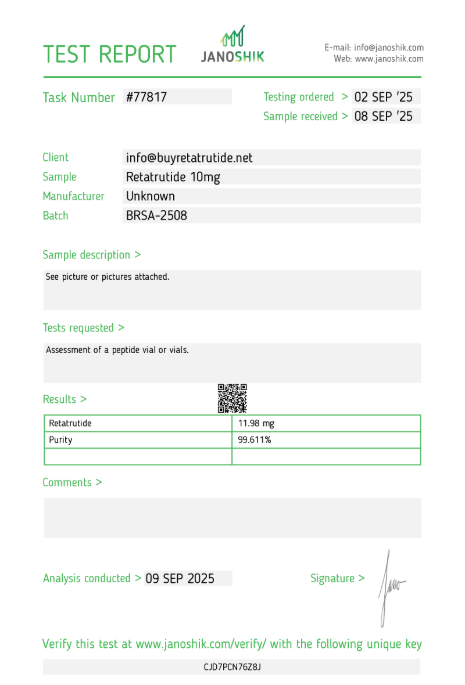

£195.00Independently verified COA. UK stock, worldwide delivery. For lab use only.

Recommended Starting Dose

When reviewing the available clinical data, the recommended starting dose of retatrutide is not something a researcher can choose freely but instead follows the structured design of the phase 2 studies. In these trials, dosing was deliberately conservative at the outset in order to balance efficacy with tolerability. Subjects enrolled in weight management and metabolic health trials typically began on the lowest administered dose, which was 2 mg once weekly via subcutaneous injection. This careful initiation was designed to reduce the likelihood of early gastrointestinal events such as nausea, a well known class effect seen with GLP-1 receptor agonists and similar multi agonists. By starting at 2 mg and then stepping upwards, researchers created a controlled environment where both safety and pharmacodynamic effects could be measured with precision.

The reason this structured beginning matters is because retatrutide dosing is multi layered. Unlike over the counter compounds, investigational peptides undergo strict protocols that determine not only the amount delivered but also the timing, frequency, and duration of each dose. The 2 mg starting point was therefore never meant as an “effective dose” for long term use. Rather, it served as a gentle entry, preparing participants for subsequent escalations in line with tolerability. In other words, this initial stage was less about immediate outcomes and more about building a stable foundation for the higher doses that followed.

Importantly, some trial arms explored slightly different initiation strategies. For example, in the NEJM-published phase 2 trial, subjects were randomised to receive 2 mg, 4 mg, 8 mg, or 12 mg once weekly. Even in these cases, escalation schedules were applied, meaning that individuals did not simply jump into the higher tiers. Instead, most arms began with the lowest dose level and then advanced stepwise. This approach allowed investigators to directly compare how gradual increases influenced both safety and efficacy outcomes. From a research perspective, it highlights the importance of treating dosage as a dynamic pathway rather than a fixed number.

What makes this noteworthy is that the dose is not only a pharmacological decision but also a practical one. A peptide like retatrutide, with its triple agonist activity (GLP-1, GIP, glucagon), can deliver powerful effects, yet this very potency requires that the dosing remain measured and carefully managed. Researchers therefore use the concept of a “starting dose” as a form of controlled exposure, much like slowly turning up the volume on a sensitive sound system rather than blasting it at full power. By easing subjects in, trial designers safeguarded participants while still enabling meaningful data collection on metabolic changes, appetite regulation, and weight reduction.

Another important feature of the trial design is that the starting dose always remained once weekly. There were no twice weekly or daily regimens in these studies, which reflects an intentional effort to make the schedule manageable for participants. Weekly injections reduce variability, ensure compliance, and simplify monitoring of biomarkers like glucose, insulin, and body weight. For laboratory research, this once weekly rhythm provides consistency and comparability across subjects. It is part of what makes retatrutide unique compared to older molecules, as its half-life supports extended intervals without the need for daily administration.

From a broader standpoint, starting with the 2 mg dose also set the stage for understanding long-term tolerability. Adverse events reported in the first few weeks were generally mild to moderate, and their incidence tended to lessen as dosing escalated and subjects adapted. By structuring trials in this way, researchers were able to balance the competing demands of safety monitoring, patient comfort, and the scientific need to push towards therapeutically relevant doses. This is why the concept of a “starting dose” in the retatrutide program is best viewed as a methodological tool rather than a recommendation for end use.

Disclaimer: All references to retatrutide dosage and trial design are provided solely to summarise published research. Retatrutide remains an experimental compound not authorised for medical use. Any product available through research suppliers is strictly intended for laboratory investigation only, not for human consumption. This overview is for educational purposes to illustrate how scientists approached dosing in clinical trials, not for guidance on self administration or therapy.

Titration and Dose Adjustments

One of the defining features of the retatrutide dosing strategy observed in clinical trials is its careful stepwise titration. Rather than prescribing a single fixed dose from the outset, investigators used a gradual escalation model to help participants adapt to the compound’s potent triple agonist activity. This approach reflects lessons learned from earlier GLP-1 receptor agonists, where gastrointestinal side effects often limited compliance if higher doses were given immediately. In the case of retatrutide, titration was built into the protocol as a core safety measure and as a way to observe pharmacological responses across different increments.

In the pivotal phase 2 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, subjects typically began with a 2 mg once weekly starting dose. Over the course of several weeks, that amount was systematically increased to 4 mg, 8 mg, or eventually 12 mg, depending on the randomised arm. The escalation intervals were not arbitrary: each step was separated by several weeks to allow for monitoring of adverse events, biomarker shifts, and weight-loss trends. For example, in some arms participants advanced from 2 mg to 4 mg after four weeks, then to 8 mg after an additional four weeks, and in the highest arm moved on to 12 mg once weekly after yet another staged interval. This slow climb reflected a “low and slow” philosophy, giving the body time to adjust to the metabolic and appetite-suppressing effects of the drug.

From a research perspective, this titration process was essential for two reasons. First, it reduced the frequency and severity of gastrointestinal events such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea, which are common with incretin-based therapies. Second, it enabled investigators to track the incremental benefits of each dose level. By analysing outcomes after every escalation, researchers could determine whether improvements in weight, HbA1c, and other metabolic markers scaled linearly with dose, or whether benefits plateaued after a certain point. This type of structured escalation yields far richer data than a single fixed-dose trial would have allowed.

It is also notable that the titration schedules were preplanner and did not involve on-the-fly adjustments by participants or clinicians. Unlike in routine medical practice, where a doctor might increase or decrease a medication according to patient feedback, the retatrutide studies followed rigid escalation timelines. This ensured uniformity across participants and made the results statistically reliable. The design helped prevent bias and variability, providing a clear picture of how each dosing step influenced outcomes over time. For laboratory and academic researchers, these rigid protocols are vital for drawing robust conclusions from multi-arm studies.

Another interesting feature of the titration model is how it balanced tolerability with efficacy. By moving gradually from 2 mg to higher doses, the trial sponsors could keep dropout rates low while still pushing toward therapeutically meaningful levels. In fact, retention in the retatrutide program was relatively strong, suggesting that this stepped approach succeeded in keeping participants engaged long enough to generate reliable data. Without titration, the sudden introduction of 8 mg or 12 mg would likely have produced far more intolerances and early withdrawals, compromising the validity of the results.

From a methodological standpoint, titration also allows researchers to test the durability of response. For instance, if a participant shows significant weight reduction at 4 mg, advancing them to 8 mg can help determine whether additional benefits accrue or whether the earlier dose was already sufficient. This type of incremental adjustment gives insights into the dose-response relationship, a crucial aspect when evaluating any new investigational drug. Understanding that curve is particularly important for a multi-agonist like retatrutide, since its triple pathway activation may produce nonlinear effects that differ from those of single pathway agents.

To put it plainly, titration is less about custom tailoring and more about structured exposure. Every subject follows the same roadmap, and the roadmap itself is what generates the data. By observing a group that escalates in lockstep, scientists can chart not only average effects but also the variability within the cohort. These findings will later guide whether higher doses are truly needed for the majority or whether moderate dosing levels strike the best balance of benefit and safety.

Disclaimer: All discussion of retatrutide dosage and stepwise escalation here is a factual summary of published clinical trial design. Retatrutide is not approved for treatment and any compound offered for sale is strictly for laboratory research, not for human consumption. The details provided illustrate how titration was applied in trials to gather data; they are not guidance for therapeutic use.

Maintenance Dosage Guidelines

Once participants in the phase 2 trials had completed the initial titration steps, they entered what can best be described as the maintenance dosing phase. This stage was critical because it reflected how retatrutide performs over extended periods at steady-state exposure. Rather than focusing on short term adaptation, maintenance dosage was designed to test durability of response, consistency of metabolic improvements, and the overall safety profile of higher doses administered for many weeks. Researchers were therefore less concerned with incremental adjustments and more focused on sustaining a stable weekly regimen that would allow meaningful long-term observations.

In these studies, maintenance dosing varied depending on the trial arm. Participants could remain at 4 mg, 8 mg, or escalate to 12 mg once weekly following the titration phase. Each of these levels represented a possible long-term dose for evaluation, and investigators carefully tracked weight reduction, HbA1c changes, lipid shifts, and tolerability at each step. The design provided a broad perspective: for some individuals, moderate doses like 4 mg already produced marked weight loss and improved metabolic outcomes, while for others the higher 12 mg dose showed additional benefit. This variation underscored the importance of exploring a range of dosages rather than assuming a single “best” number.

One of the most important findings was that weight loss and metabolic improvements tended to deepen with continued weekly dosing. At the 48-week mark, those maintained on the 12 mg arm had achieved an average weight reduction exceeding 24% of baseline body weight, one of the largest effects ever reported in the obesity field. Even the 8 mg arm demonstrated impressive outcomes, with weight loss in the high teens as a percentage of baseline. Such results highlight that the maintenance dose is not just a safety exercise but directly tied to the magnitude of benefit seen over time. By keeping participants at their allocated dosage for months on end, researchers could confidently attribute sustained outcomes to the compound rather than to temporary fluctuations.

From a mechanistic standpoint, the ability of retatrutide to sustain benefits over many months likely reflects both its pharmacokinetic profile and its triple-agonist mechanism. With once weekly injections maintaining plasma exposure, the peptide could continuously act on GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors. The maintenance dosing phase thus served as a real-world stress test: could subjects tolerate months of ongoing receptor engagement without dropout or adverse safety signals? The results suggest that with gradual escalation, many participants did adapt well, allowing them to complete the long-term maintenance schedules set out by the protocol.

That said, not every individual tolerated the higher doses. Some participants at 12 mg experienced persistent nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort that made continuation challenging. This is why parallel arms at 4 mg and 8 mg were so valuable. By running multiple maintenance dosages side by side, investigators could identify tolerable thresholds for different subsets of subjects. It also underscored that more is not always better: while 12 mg delivered the largest absolute weight loss, a slightly lower dose sometimes provided an excellent balance between efficacy and tolerability.

Another critical element of the maintenance phase was metabolic durability. Researchers measured endpoints like fasting glucose, HbA1c, insulin resistance, and lipid profiles across the different doses. The data suggested sustained improvements at all maintenance levels, though again the greatest benefits aligned with the highest dosage. Importantly, adverse events did not steadily increase in proportion with the dose. Instead, they often peaked during titration and then levelled off, meaning that once participants were settled into their maintenance schedule, side effects tended to diminish rather than worsen. This pattern reinforced the value of titration before settling into long term dosing.

For laboratory researchers, these maintenance protocols provide a roadmap for how investigational compounds can be studied over time. A weekly injection schedule was maintained without alteration, ensuring consistency and simplifying statistical comparisons across groups. Such clarity is vital in experimental design, as it allows the focus to remain on pharmacology and outcomes rather than variability introduced by inconsistent schedules. It also mirrors how regulators and scientific reviewers expect to see maintenance dosage data presented: steady, reproducible, and directly tied to measurable outcomes.

Disclaimer: All references to retatrutide dosage and long term dosing schedules are based on published clinical research. Retatrutide is not an approved medication, and any material supplied is for investigative laboratory purposes only. These summaries are provided to describe how trials evaluated sustained weekly dosing and should not be interpreted as instructions for human use or therapy. Not for human consumption.

Dosage for Weight Loss vs. Metabolic Health

One of the most striking aspects of the phase 2 trials was how different retatrutide dosages produced overlapping yet distinct benefits in two related areas: body weight reduction and metabolic improvement. The study design allowed investigators to separate these effects, since participants were followed for up to 48 weeks with clear dose dependent outcomes recorded. This dual focus is important because it shows that while all doses of retatrutide influenced weight, the degree of improvement in glucose control and lipid profiles did not always track exactly with weight loss. As such, the conversation around dosing is not only about “how much weight can be lost” but also about how metabolic health shifts alongside it.

For weight management, higher doses such as 8 mg and 12 mg once weekly delivered the most dramatic results. By the end of the 48-week trial, individuals on the 12 mg maintenance dose had lost an average of more than 24% of their baseline body weight, a figure that rivals or even exceeds bariatric surgery in some cases. The 8 mg group also achieved striking outcomes, typically in the range of 17–18% reductions. By contrast, lower doses like 4 mg still produced meaningful loss, often in the low double-digit percentage range, though not to the same magnitude. These outcomes illustrate a clear dose–response curve for weight management, where escalating weekly dosing correlates strongly with greater body weight reduction.

When examining metabolic health markers, the picture becomes more nuanced. Even the lower dosage groups, such as 4 mg, demonstrated measurable improvements in fasting glucose, insulin resistance, and HbA1c. These shifts were often significant enough to suggest clinical relevance in the context of type 2 diabetes management. Interestingly, while weight loss outcomes continued to rise sharply with higher doses, the incremental benefits for glucose control and lipid levels appeared to plateau somewhat. This means that in terms of pure metabolic correction, moderate dosing was already delivering much of the effect, while higher doses primarily amplified weight loss outcomes.

This divergence has practical implications for how scientists think about retatrutide dosage. If the research question is weight loss alone, pushing toward the maximum tolerated dose seems logical, since the relationship between dosing and body fat reduction remains strong. But if the focus is metabolic correction, such as reducing HbA1c or improving insulin sensitivity then lower or mid range doses might already be sufficient. This balance underscores why multiple trial arms were necessary: without testing a range of dosages, investigators would not have uncovered these differences in outcome patterns.

Another layer to consider is tolerability. While 12 mg weekly showed unmatched weight loss, it also produced the highest incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. Some participants were unable to continue at this dose for the full duration, reducing long-term retention. By contrast, the 4 mg and 8 mg doses were associated with fewer adverse events and higher completion rates, even though their weight-loss outcomes were somewhat lower. This again highlights the importance of distinguishing between weight-focused and metabolic-focused endpoints when interpreting retatrutide dosing strategies.

From a mechanistic standpoint, these findings make sense. The GLP-1 component of retatrutide drives appetite suppression and slows gastric emptying, contributing to weight loss, while the GIP and glucagon activity influence insulin sensitivity, glucose handling, and energy expenditure. As the dose increases, appetite suppression intensifies, but metabolic benefits from receptor engagement may already be near-maximal at intermediate dosing levels. In other words, the pathways plateau at different points, creating a scenario where more dosage drives further weight loss without proportionally increasing metabolic benefit.

For researchers, the key takeaway is that weight loss and metabolic correction are related but not identical outcomes. Designing future studies may require careful attention to which endpoint is primary, as that will dictate whether a lower, moderate, or higher dose is emphasised. The phase 2 data suggest that if the priority is body weight reduction in obesity without diabetes, higher dosing arms like 12 mg may be appropriate for exploration. If the priority is glycaemic control or cardiometabolic health, then moderate dosages like 4 mg or 8 mg might already offer the majority of the benefit without excess side effect burden.

Disclaimer: These comparisons of retatrutide dosage in relation to weight loss and metabolic health are strictly based on published trial data. Retatrutide is not approved for therapy and any material available commercially is for laboratory research only, not for human consumption. The descriptions above illustrate how dosing influenced outcomes in trials and are not intended as instructions for treatment use.

Factors Influencing Individual Dose

Although the phase 2 program for retatrutide applied fixed escalation schedules, it is clear that many variables influence how any individual might respond to a given dose. From a research perspective, these factors help explain why some participants tolerated 12 mg weekly with strong outcomes while others did better at 4 mg or 8 mg. Understanding these variables does not mean adjusting dosing in practice since the trials followed strict protocols but it does provide useful context for interpreting results and planning future studies. Ultimately, retatrutide dosage is shaped by more than just pharmacology; it intersects with physiology, baseline health, and trial design.

One of the most obvious factors is baseline body weight. Participants with higher starting body mass indexes often demonstrated more dramatic absolute weight reductions, even if the percentage change was similar to those with lower baseline weight. This matters when considering dose-response relationships: a heavier subject at 8 mg may lose more kilograms than a lighter subject at 12 mg, even though the relative loss looks different on paper. For researchers, this highlights the need to stratify outcomes not only by dose but also by starting weight, ensuring that comparisons across arms are meaningful.

Metabolic status is another influential variable. Participants with type 2 diabetes tended to show rapid improvements in glucose markers even at moderate doses, sometimes without requiring escalation to the maximum levels. By contrast, participants without diabetes often required higher dosing to see the same scale of metabolic benefit. This suggests that Retatrutide’s activity on GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon pathways interacts with underlying insulin sensitivity. In future trials, tailoring the studied dosage arms to participant subgroups may help refine the picture of how metabolic health shapes response.

Tolerability also plays a central role. Gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, diarrhoea, or vomiting were the most common adverse events in the phase 2 program, and they occurred more frequently at higher doses. Some participants withdrew from the 12 mg arm because they could not tolerate the escalation, whereas most completed the 4 mg and 8 mg dose levels. This variation shows how individual sensitivity to incretin and glucagon signalling can set practical limits on the maximum dosage a person can endure, even in a tightly controlled research setting. Retention rates, therefore, become an indirect marker of tolerability across doses.

Age, sex, and genetic factors may also influence response, though these were not primary endpoints in early studies. Still, evidence from related GLP-1 agonists suggests that pharmacogenomics and demographic characteristics can shape absorption, metabolism, and receptor sensitivity. It is reasonable to expect that similar dynamics could apply with retatrutide, meaning that one participant may require a higher dose to achieve the same outcomes as another. Future studies may investigate these variables more directly, potentially identifying biomarkers that predict optimal dosing ranges.

Trial design itself is another determinant. Because participants in the published phase 2 study escalated in fixed intervals, their eventual “maintenance” dose was dictated by the randomised arm rather than personal adaptation. This means that outcomes across individuals reflect both biology and study design. A participant who tolerated 4 mg well might have done equally well on 8 mg if given the chance, but the rigid escalation plan did not allow such flexibility. This methodological choice ensures cleaner data but also means that individual responses to different dosages remain partially unexplored.

Finally, duration of exposure influences results. Participants on the same dosing level for longer periods generally showed more sustained improvements, reinforcing that retatrutide works cumulatively over time. A 12-week snapshot may underestimate the full effect of a given dose, whereas the 48-week results highlight just how powerful extended maintenance can be. Time, therefore, is as much a factor as milligrams, and both must be considered when interpreting the relationship between retatrutide dosage and outcomes.

Disclaimer: These observations about variables affecting retatrutide dosing are drawn from trial data and related literature. Retatrutide is not an approved treatment, and any reference to dose or dosage is for educational purposes only. Compounds labelled as retatrutide available for purchase are intended solely for laboratory research, not for human consumption. This content summarises factors that researchers consider when evaluating study results, not instructions for individual use.

Missed Dose Instructions

Every structured study of investigational compounds includes a plan for handling missed administrations, and the retatrutide dosage trials were no exception. Because dosing was fixed at once-weekly intervals, researchers had to anticipate what would happen if a participant missed a scheduled injection. This is a common challenge in long-term clinical research: life circumstances, illness, or logistical issues can interfere with compliance. Understanding how missed doses were handled in the phase 2 program provides clarity about how investigators maintained data integrity while safeguarding participants.

According to the trial protocols, the general rule was that if a dose was missed, it could still be administered within a defined window, usually several days after the scheduled date, without disrupting the escalation plan. If more time had passed, the participant might skip that week entirely and resume their normal schedule at the next appointed time. This structure ensured consistency while also acknowledging that minor lapses were inevitable in a 48-week study. By documenting each missed dose and its timing, researchers could adjust their analyses to account for slight irregularities in exposure.

From a pharmacological perspective, the once-weekly schedule is supported by Retatrutide’s extended half-life, which allows therapeutic levels to remain in circulation for days after administration. This property means that a single missed dose is less disruptive than it would be with a daily medication. Participants who delayed their injection by several days still maintained a degree of receptor coverage, reducing the risk of large fluctuations in appetite suppression or metabolic outcomes. The trial design thus built on the pharmacokinetic strengths of the compound, allowing for flexibility in real-world scenarios of non-adherence.

Nevertheless, repeated missed doses presented a different challenge. Consistency was key for generating robust data on weight loss and metabolic health, and subjects who missed multiple weekly administrations risked reducing the accuracy of the results. In such cases, participants might be withdrawn from the study or moved into a different analysis group to ensure the data remained reliable. This illustrates how trial protocols treat missed dosing not only as a logistical matter but also as a methodological one: too many lapses can compromise both safety and statistical validity.

Importantly, the phase 2 study did not allow participants to “double up” on their next scheduled injection if they missed one. Escalation steps were carefully timed, and safety monitoring was built around those intervals. Administering two doses at once would have contradicted the protocol and introduced unnecessary risk. Instead, the structured plan of either catching up within a defined window or skipping altogether maintained the scientific integrity of the program. This reinforces the point that retatrutide dosing in trials is about consistency and safety, not improvisation.

For researchers, documenting missed dosage events is almost as important as recording completed ones. By noting exactly when and why a scheduled administration did not occur, investigators could better interpret the variability in outcomes. For example, if a participant’s weight reduction stalled, knowing that they had missed two doses could explain the deviation without undermining the validity of the compound itself. Careful tracking of missed dosing therefore served both scientific and safety purposes, providing context for individual results and preserving the overall quality of the trial dataset.

It is also worth noting that the flexibility in handling missed doses likely improved participant retention. Knowing that a late injection could still be valid within a certain timeframe may have reduced stress and kept individuals engaged in the study. Strict, unforgiving schedules often lead to higher dropout rates, whereas protocols that allow for minor lapses tend to support better long-term compliance. Retatrutide’s weekly rhythm, combined with its forgiving pharmacokinetics, proved well-suited to this balance of rigour and flexibility.

Disclaimer: The information above summarises how missed retatrutide doses were managed in clinical trial protocols. These details are provided solely for educational purposes and to explain how researchers preserve data quality in long-term studies. Retatrutide is not approved for medical use, and any compound supplied under this name is for laboratory research only, not for human consumption. These descriptions should not be interpreted as instructions for individual use or therapeutic guidance.

Safety and Monitoring

Every investigational program has two pillars: efficacy and safety. For retatrutide dosing, the safety and monitoring component was just as important as the weight-loss and metabolic outcomes. Because this compound engages three distinct hormonal pathways-GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon-investigators built intensive monitoring schedules into the phase 2 trial designs. This ensured that each dose escalation could be evaluated not only for its potential benefit but also for its tolerability and risk profile. Monitoring was especially vital during the early weeks of titration, when gastrointestinal side effects were most likely to occur.

The most frequently reported adverse events were gastrointestinal in nature, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and constipation. These events tended to cluster around the weeks when the dose was increased, particularly when subjects moved from 2 mg to 4 mg or later from 8 mg to 12 mg once weekly. Researchers recorded both the incidence and severity of these effects, and most were graded as mild to moderate. Importantly, the frequency of these side effects declined as participants settled into their maintenance dosage, suggesting that adaptation occurred with ongoing weekly dosing.

Beyond gastrointestinal issues, safety monitoring also included vital signs, laboratory bloodwork, and imaging. Subjects underwent regular checks of fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipid levels, and liver enzymes. Because retatrutide activates glucagon receptors, investigators were particularly attentive to hepatic markers and potential changes in liver fat content. Monitoring also extended to heart rate and blood pressure, as incretin-based therapies can influence cardiovascular physiology. By pairing each dose level with a thorough battery of measurements, researchers could identify whether risks escalated alongside higher dosing.

Another critical safety observation was hypoglycaemia risk. Although retatrutide influenced glucose metabolism strongly, clinically significant hypoglycaemic events were rare in the phase 2 studies, particularly among participants without type 2 diabetes. This suggested that the compound’s mechanism of action provided improvements in insulin sensitivity and glucose handling without dramatically overshooting into dangerous lows. Nevertheless, monitoring for symptomatic hypoglycaemia remained an integral part of the protocol at every dosage level, especially for participants also using background glucose-lowering therapies.

Safety monitoring also required a longer-term perspective. The 48-week duration allowed investigators to track durability of tolerability. Participants who had adapted to their maintenance doses early in the study often reported fewer side effects over time, supporting the concept that Retatrutide’s tolerability profile improves with continued weekly dosing. Dropout rates were highest in the early titration phases and decreased as individuals moved into the stable maintenance phase. This trend reinforces the importance of starting low and escalating slowly-a strategy that mitigates side effects and helps subjects remain in the study long enough to generate meaningful data.

Researchers also incorporated regular safety reviews by independent monitoring boards. These groups had the authority to halt dosing for individual participants or even stop trial arms if concerning patterns emerged. Such oversight is standard for high-impact investigational drugs and ensured that all observed safety signals were evaluated impartially. No major safety red flags caused trial termination, which was encouraging, but the presence of independent oversight adds credibility to the findings and demonstrates the cautious approach taken with each dose.

From a methodological standpoint, safety and monitoring were not separate from efficacy-they were intertwined. For example, weight loss outcomes had to be weighed against tolerability: a 12 mg weekly dose produced the most dramatic reductions in body weight but also the highest rate of gastrointestinal complaints. By contrast, 4 mg and 8 mg dosages produced slightly lower weight loss but were better tolerated, with fewer adverse events. This balance between efficacy and safety is central to interpreting the data and will likely shape how future studies prioritise one endpoint over the other.

Disclaimer: The information above reflects how retatrutide dosing was monitored for safety in published clinical trials. It is provided for educational and research discussion only. Retatrutide is not an approved therapy, and any compound offered under this name is intended solely for laboratory investigation, not for human consumption. Descriptions of safety monitoring procedures illustrate trial methodology and should not be interpreted as medical guidance.

Order Retatrutide Online

Available in 10mg vials. Select your pack size and checkout securely below.

-

Reta 10mg 3 Vials

£195.00Independently verified COA. UK stock, worldwide delivery. For lab use only.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the starting retatrutide dose used in trials? In phase 2 studies, participants generally began on a 2 mg once-weekly dose. This was the lowest starting point to reduce side effects before moving on to higher doses.

- How was retatrutide dosing escalated? Subjects typically increased from 2 mg to 4 mg, then to 8 mg, and in some arms up to 12 mg once weekly, following fixed timetables set by the research protocol.

- What was the highest retatrutide dosage studied? The maximum dose tested in published trials was 12 mg once weekly. This arm produced the largest average weight loss but also the highest rate of gastrointestinal side effects.

- How often was retatrutide administered? All trial dosing was once weekly by subcutaneous injection. No daily or twice-weekly schedules were evaluated.

- What weight loss was observed at different dosages? At 48 weeks, the 12 mg arm produced average losses of about 24% of baseline weight, 8 mg gave reductions of ~17–18%, and 4 mg delivered double-digit but more moderate decreases.

- Did metabolic health improve at lower doses? Yes. Even 4 mg weekly improved fasting glucose, insulin sensitivity, and HbA1c, showing that metabolic benefits can appear before maximum weight-loss effects.

- What happened if a dose was missed? If a weekly dose was missed, protocols allowed a late injection within a certain window or skipping to the next scheduled administration. Double dosing was not permitted.

- Were safety issues linked to dosing? Most side effects were gastrointestinal and occurred during titration. They were more common at higher dosages, but usually declined once subjects adapted.

- Is retatrutide dosage adjusted individually? In trials, dosing followed fixed schedules, not personalised adjustments. However, individual factors such as tolerability and baseline health influenced outcomes.

- Can higher doses always be expected to give better results? Not necessarily. While higher dosages produced greater weight loss, moderate doses already provided strong metabolic improvements with fewer side effects.

- How long did participants stay on their maintenance dose? Subjects were maintained at their assigned dose for up to 48 weeks, allowing researchers to measure durability of response and long-term tolerability.

- What factors influenced retatrutide dosing outcomes? Baseline weight, metabolic status, tolerability, trial design, and treatment duration all shaped how participants responded to different dosages.

- Were any severe adverse events reported? Serious safety events were rare. Most adverse events were mild to moderate and gastrointestinal in nature, resolving as dosing stabilised.

- Is this dosing information medical advice? No. These descriptions only summarise clinical trial protocols. Retatrutide is investigational and supplied for laboratory research only, not for human consumption.

- What makes retatrutide dosing unique compared to older drugs? Its triple-agonist activity and once-weekly schedule distinguish it from older incretin drugs, requiring carefully planned titration to balance efficacy and safety.

Compare Dosing Protocols

Weekly Injectable Dosing

- Semaglutide – 0.25-2.4mg weekly

- Tirzepatide – 2.5-15mg weekly

- Dulaglutide – 0.75-4.5mg weekly

Daily Injectable Dosing

- Liraglutide – 0.6-3mg daily

- Exenatide – 5-10mcg twice daily

Oral Dosing Options

- Rybelsus – Oral semaglutide

- Orforglipron – Oral GLP-1 in trials

Calculate your dose with our dosage calculator