Overview

Retatrutide is an investigational therapy that represents a new generation of metabolic drugs. Unlike single hormone treatments such as semaglutide, this compound combines three separate signals in one peptide: GLP-1, GIP and glucagon. By targeting multiple receptors that influence appetite, insulin release, energy expenditure and fat metabolism, researchers believe it can deliver deeper and more sustained improvements in weight and metabolic health. Since the first Retatrutide clinical trials began in 2021, the development programme has moved rapidly, producing several highly discussed results in the medical literature and now progressing into global Phase 3 testing.

The first major evidence that retatrutide could be a step change in obesity care came in 2023, when the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of a large Phase 2 trial. Participants with obesity who received the highest doses lost on average more than 24 percent of their starting body weight after 48 weeks of therapy (NEJM publication, PubMed record). These results not only exceeded expectations but also outperformed existing incretin therapies tested over similar durations. The story quickly reached wider coverage, with outlets such as MedPage Today highlighting the findings for both clinicians and the public (MedPage summary).

In parallel, retatrutide was studied in people living with type 2 diabetes. A Phase 2 trial published later that same year in The Lancet showed substantial reductions in HbA1c and fasting glucose, alongside clinically meaningful weight loss. These dual benefits have raised hopes that the drug might simultaneously improve glycaemic control and address obesity, two conditions that frequently overlap and compound health risks (Lancet paper, PubMed abstract, ScienceDaily coverage).

Beyond weight and blood sugar, attention has turned to the liver. A sub study published in Nature Medicine in 2024 explored retatrutide in people with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Participants showed marked reductions in liver fat content and improvements in markers linked to

inflammation and fibrosis risk (Nature Medicine article, PubMed entry). These results have encouraged further exploration into whether the therapy could address liver complications that often accompany obesity and diabetes.

Building on the strength of Phase 2 outcomes, Lilly has launched the TRIUMPH programme, a global Phase 3 effort that includes studies in obesity, diabetes, sleep apnoea and cardiovascular outcomes. Recruitment began in 2023 and key results are expected later this decade (company announcement, ClinicalTrials.gov listing). Together, these studies are designed to establish whether the impressive Phase 2 findings can be replicated at scale and translated into long-term clinical benefit.

This article brings together the available evidence from Phase 1 exploratory work, Phase 2 Retatrutide clinical trials in obesity, diabetes and liver disease, and the ongoing Phase 3 programme. It is intended as a structured research overview rather than medical advice. Retatrutide remains an experimental compound, unapproved by regulatory agencies, and should not be used outside controlled clinical

studies.

Ready to Order?

Choose your preferred amount below, fast shipping and secure checkout.

-

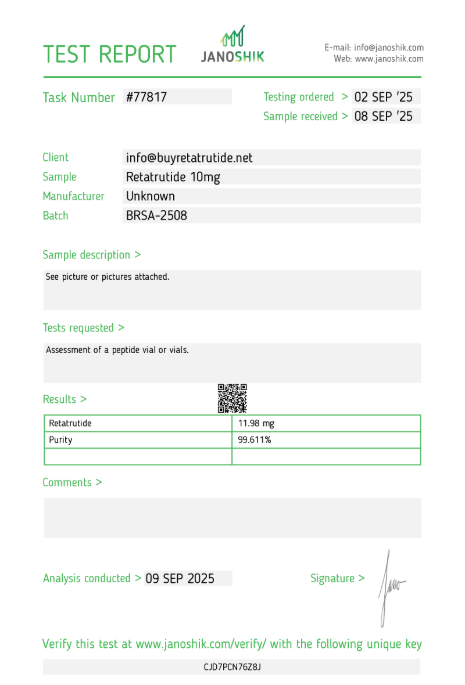

Reta 10mg 3 Vials

£195.00Independently verified COA. UK stock, worldwide delivery. For lab use only.

Phase 1: First-in-Human

Every new drug development programme begins with the careful process of first-in-human testing, and retatrutide was no exception. Before moving into large-scale studies, researchers needed to answer some fundamental questions: how the compound behaves in the body, whether it can be tolerated at different doses, and if there are any safety concerns that would prevent further development. This early stage of clinical research began around 2021 and enrolled healthy volunteers under tightly controlled conditions. The goal was to measure pharmacokinetics, meaning how the drug is absorbed, distributed and cleared, as well as pharmacodynamics, which tracks its biological effects on appetite hormones and glucose regulation.

The Phase 1 programme was structured in a classic dose-escalation design. Small groups of participants were given a starting dose, and if no significant safety issues were observed, subsequent groups received incrementally higher amounts. This gradual approach allowed scientists to map out a safe dosing range and to see how long retatrutide stayed active in the bloodstream. Early results suggested the compound had a half-life that supported weekly injections, a key feature that aligns with how other incretin-based drugs are dosed. Reports from investigators indicated that the drug engaged all three intended receptors effectively, producing measurable shifts in biomarkers even at relatively modest doses.

Safety monitoring was the most important priority in this phase. As expected with incretin therapies, the most frequently reported side effects were gastrointestinal, including mild nausea, a sense of fullness, and occasional diarrhoea. These events were usually short-lived and tended to decrease as participants adjusted to the treatment. Crucially, no serious adverse events or dose-limiting toxicities were observed, and no participants discontinued due to safety issues. This profile gave researchers confidence that larger, longer studies could proceed. The overall safety picture looked similar to what had been seen with GLP-1 and dual agonists such as Tirzepatide, suggesting that adding a third receptor target did not fundamentally change tolerability in the early stages.

Although Phase 1 data are not always published in high-profile journals, details of the retatrutide studies can be found in regulatory trial registries. For example, ClinicalTrials.gov entry NCT04867785

outlines one of the multiple-ascending dose studies conducted by Lilly. Abstracts presented at international diabetes and endocrinology meetings have also shared preliminary insights into pharmacological activity, confirming that retatrutide produced early reductions in appetite and modest short-term effects on glucose levels even at lower doses (scientific meeting abstract).

While these results did not generate the same level of media attention as later Phase 2 retatrutide clinical trials for obesity, they were critical for establishing the foundation of the development programme. Without the confidence gained in Phase 1, regulators would not have allowed retatrutide to advance into larger studies involving hundreds of patients with obesity, diabetes or liver disease. The early confirmation that the compound could be administered once weekly, was generally well tolerated, and delivered the expected biological activity was enough to greenlight the move into more ambitious clinical testing.

In summary, the Phase 1 studies achieved what they were designed to do. They demonstrated that retatrutide was safe to administer in humans, established a suitable dosing schedule, and provided evidence that the triple-agonist mechanism was active in real patients. These early retatrutide trials may not capture public headlines, but they were a decisive moment in confirming that this multi-pathway strategy was viable and worthy of investment. With this groundwork complete, Lilly advanced quickly into Phase 2 retatrutide clinical trials where questions of efficacy, weight loss potential, and disease-specific outcomes could be answered on a larger scale.

Phase 2 (Obesity): Study Design

Once the first-in-human testing established safety and tolerability, retatrutide was advanced into a pivotal Phase 2 programme targeting obesity without diabetes. This stage of research was designed to determine whether the drug could produce meaningful and sustained weight loss in a diverse adult population, and whether the benefits outweighed the risks observed in early studies. The trial, sponsored by Eli Lilly, recruited more than 300 participants who were either overweight or had obesity, with body mass indexes typically above 30. The study was randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled, which is the gold standard approach for clinical testing of new therapies.

Participants were assigned to one of several retatrutide dose groups or to placebo. The dosing strategy was structured to explore a wide range of responses, from low weekly doses that were expected to have modest effects through to higher weekly doses aimed at producing maximal weight reduction. Importantly, the trial used a gradual dose-escalation schedule to improve tolerability. Starting doses were small and then increased stepwise every few weeks, which is a common technique to minimise gastrointestinal side effects associated with incretin therapies. Treatment continued for 48 weeks, long enough to capture not only early weight loss but also whether the trajectory was sustained across nearly a full year.

The trial was published in mid-2023 in the New England Journal of Medicine and is indexed on PubMed. The design included multiple active treatment arms, typically ranging from 1 mg to 12 mg once weekly, allowing researchers to plot a dose–response curve. The placebo group received matching injections on the same schedule to maintain blinding. To ensure balanced comparisons, participants were stratified by baseline weight and sex, factors known to influence outcomes in obesity studies.

Alongside body weight, the investigators measured several secondary endpoints. These included waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting glucose, lipid profiles, and patient-reported quality of life measures. Safety endpoints were also tracked closely, with a special focus on gastrointestinal events, cardiovascular parameters and liver enzymes. Such a broad set of outcomes ensured that the trial would capture not only the headline figure of weight loss but also the wider impact of retatrutide on metabolic health.

Lifestyle intervention was standardised across the groups to reduce confounding. All participants received counselling on diet and physical activity, which reflects real-world recommendations but also provides a baseline of behavioural support. The aim was not to replace lifestyle measures with medication, but to examine how much incremental benefit retatrutide could provide beyond standard advice. This was important because in obesity trials, changes in lifestyle alone can sometimes drive weight fluctuations, and controlling for this helps isolate the effect of the drug.

The Phase 2 obesity study was conducted across multiple international sites to capture a broad demographic mix. This improves the generalisability of the results and reduces the chance that findings are limited to one region or subgroup. Participants were monitored regularly through in-person clinic visits, laboratory testing, and safety assessments. Adherence to dosing schedules was carefully tracked to ensure accurate interpretation of the data.

The trial design has been praised for its robustness and its ability to generate clear, interpretable outcomes. By using a large sample size, multiple dose groups, and nearly one year of follow-up, the study created a strong foundation for evaluating efficacy. It also provided essential information for designing Phase 3 studies, particularly around optimal dosing strategies and escalation schedules. External summaries, such as those published by MedPage Today, emphasised that the design anticipated many of the practical issues clinicians would face when prescribing retatrutide in routine care.

In summary, the Phase 2 obesity study was not just a proof of concept but a carefully constructed investigation intended to define how retatrutide should be used in the clinic if eventually approved. It mapped out the relationship between dose and effect, measured multiple aspects of metabolic health, and ensured safety was monitored with rigour. With this strong framework, the trial was well-positioned to deliver meaningful results, which were later reported in 2023 and quickly became some of the most discussed data in the field of obesity research.

Phase 2 (Obesity): Outcomes & Results

The Phase 2 obesity study delivered some of the most eye-catching numbers seen in metabolic medicine. Over a 48 week treatment window, participants on the highest retatrutide doses achieved average weight reductions greater than 24 percent of baseline. These findings were reported in the peer reviewed New England Journal of Medicine and indexed on PubMed, with independent coverage for clinicians via MedPage Today.

Weight change followed a clear dose response pattern. Lower weekly doses produced solid reductions that commonly reached double digit percentages, while mid and upper ranges drove progressively larger declines. The study used gradual dose escalation to improve tolerability, so the curve of weight loss typically steepened as participants reached their maintenance dose and then continued at a steadier pace through the remainder of the year. By the end of the observation period, separation between active arms and placebo was wide and clinically meaningful.

The trajectory of loss mattered as much as the magnitude. Most participants saw early movement on the scale within the first few months, followed by steady reductions as dosing settled. That pattern suggests the triple receptor mechanism is not only suppressing appetite but also shifting energy balance over time. In practical terms, the curve looks sustainable within the constraints of a long study and aligns with how incretin based therapies tend to work in routine care.

Improvements were not limited to the scale. The investigators reported favourable shifts in waist circumference, fasting glucose, and markers of insulin sensitivity, alongside beneficial trends in lipid measures. Blood pressure moved modestly in the right direction in several treatment arms, and patient reported outcomes indicated gains in daily function and energy. Taken together, the secondary endpoints painted a consistent picture of broader metabolic improvement rather than a single isolated weight effect. These signals are summarised in the NEJM article and mirrored in lay summaries like ScienceDaily.

Safety and tolerability were closely tracked. As expected for therapies that engage incretin pathways, gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common events. Nausea, occasional vomiting, softer stools or diarrhoea, and reduced appetite occurred more often during the escalation period and generally eased once participants stabilised on their maintenance dose. Completion rates were high, and discontinuations for adverse events were relatively uncommon in the context of a year long study. No unexpected safety patterns emerged that would block progression to later phases, which is reflected in the subsequent move into Phase 3.

Subgroup analyses suggested the effect was broadly consistent across sexes and baseline weight categories, with the absolute percentage change largely tracking the administered dose. While the study was not powered for head to head comparisons with other medicines, the scale of reduction compares favourably with results reported for single pathway agents over similar durations. That context, together with the multi endpoint gains, is part of why this dataset drew such intense interest across the field.

It is also worth noting that the trial included standardised diet and activity guidance for all arms. That design choice helps isolate the contribution of the medicine itself, because any lifestyle effect should be balanced across groups. The remaining gap between retatrutide and placebo therefore represents an incremental benefit above and beyond usual counselling, which strengthens the case that the mechanism is driving the outcome.

In summary, the Phase 2 obesity results show large, dose related weight reduction, improvements across key metabolic markers, and a safety profile that is manageable with gradual escalation. These outcomes, documented in the primary publication and corroborated through PubMed indexing and reputable summaries, provided the evidence base Lilly needed to proceed into large scale confirmatory studies. Retatrutide remains investigational and is not approved for clinical use; the data reviewed here should be understood within a research context only.

Phase 2 (Type 2 Diabetes): Outcomes

Following the obesity trial, retatrutide was tested in people living with type 2 diabetes to understand whether the triple receptor mechanism could improve glucose control alongside weight management. This Phase 2 study enrolled adults with established type 2 diabetes who were either inadequately controlled on diet and exercise alone or were taking stable doses of metformin. The design was once again randomised, double blind and placebo controlled, ensuring robust comparisons across groups. Participants received different weekly doses of retatrutide over the course of 36 weeks, with escalation schedules built in to improve tolerability.

The main results were published in late 2023 in The Lancet and are also available through PubMed. The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c, a measure of average blood glucose over several months. Participants receiving higher doses of retatrutide achieved reductions in HbA1c approaching 2 percentage points compared to baseline, a scale of improvement typically associated with combination therapy. Even lower doses produced clinically meaningful declines, and all active groups performed better than placebo.

Weight reduction was a major secondary endpoint. Despite the shorter 36 week duration compared with the obesity study, participants still lost substantial amounts of weight. At higher doses, average losses exceeded 15 percent of baseline, and even at lower doses the majority of patients lost between 7 and 10 percent. These results underscored that Retatrutide’s weight lowering effect extends into populations with diabetes, where weight management is often more challenging due to insulin resistance and medication interactions.

The trial also measured additional markers of metabolic health. Fasting glucose declined in parallel with HbA1c, and many patients were able to reduce or stabilise their background therapies without loss of control. Insulin sensitivity markers improved, and reductions in liver fat were noted in subgroups that underwent imaging studies. Lipid parameters, including triglycerides and LDL cholesterol, showed favourable trends, though the trial was not powered to definitively assess cardiovascular outcomes. These broad effects suggest that retatrutide may help address multiple facets of metabolic syndrome beyond glycaemia alone.

Safety findings were consistent with those seen in the obesity trial. Gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common adverse events, particularly during dose escalation. Nausea, transient diarrhoea and occasional vomiting were reported, but most episodes were mild or moderate in intensity. A small proportion of participants discontinued due to side effects, but overall tolerability was acceptable for a study of this size and length. No unexpected safety concerns emerged, and cardiovascular monitoring showed no adverse signals. As in other incretin trials, gallbladder related events were monitored, though they remained infrequent.

The study was not designed for head to head comparisons, but when viewed against existing treatments it highlighted the potential of a triple agonist approach. The degree of HbA1c reduction exceeded what is typically achieved with GLP-1 therapy alone and was coupled with greater weight loss. These dual outcomes are especially relevant because many people with type 2 diabetes require both glucose control and weight management. Commentators on platforms such as ScienceDaily emphasised that retatrutide may represent a future option that simplifies treatment by combining these goals in one therapy.

In summary, the Phase 2 type 2 diabetes study demonstrated that retatrutide can deliver significant reductions in HbA1c, substantial weight loss, and improvements across a range of metabolic markers, with a safety profile that mirrors other incretin based drugs. These findings confirmed that the benefits observed in people without diabetes also apply to those with the condition, setting the stage for larger Phase 3 retatrutide clinical trials that will examine long term outcomes and potential cardiovascular benefits. The results strengthened confidence in the therapeutic concept and justified further investment in the TRIUMPH programme now underway.

Phase 2a (MASLD/MASH): Liver Outcomes

Beyond weight and glucose, investigators have been interested in whether retatrutide can influence liver health. Many people with obesity or type 2 diabetes also develop metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, known as MASLD, which can progress to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, or MASH. These conditions are characterised by the build-up of fat in the liver, inflammation, and over time, fibrosis that increases the risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer. At present, there are no approved medicines specifically for MASLD or MASH, making this an important area of research.

Lilly incorporated a sub study within the Phase 2 retatrutide programme to evaluate these effects. Patients enrolled had obesity and type 2 diabetes, and a subset underwent imaging with MRI-PDFF (proton density fat fraction), a technique that quantifies liver fat content. Some participants also provided biopsies, allowing direct assessment of histological changes in inflammation and fibrosis risk. The treatment duration was 48 weeks, mirroring the main obesity protocol, and patients were followed for safety and metabolic outcomes in parallel.

The results, published in 2024 in Nature Medicine and listed in PubMed, showed marked reductions in liver fat among patients receiving retatrutide. Depending on the dose, reductions of more than 70 percent from baseline liver fat were reported, with a substantial proportion of patients achieving normalisation of liver fat levels. These findings were far greater than what is typically seen with lifestyle measures alone and highlight the broad metabolic reach of triple agonist therapy.

Beyond fat reduction, exploratory endpoints suggested improvements in markers linked to inflammation and fibrosis. Blood tests such as ALT and AST trended downward in many participants, while non-invasive scores like the Fibrosis-4 index improved compared with placebo. A smaller number of biopsy samples indicated reductions in ballooning and inflammatory activity, though the study was not powered to provide definitive conclusions on histological endpoints. Still, the signals were encouraging enough to warrant larger dedicated trials in MASLD and MASH populations.

Safety outcomes in the MASLD sub study were consistent with the broader programme. Gastrointestinal symptoms remained the most common adverse events, but no additional liver safety concerns were identified. This was a critical finding because some metabolic therapies in the past have raised concerns about hepatotoxicity. In the case of retatrutide, the data suggested not only an absence of harm but a potential therapeutic effect on the underlying disease process.

These findings drew interest from the hepatology community. Summaries in outlets such as Healio Hepatology highlighted the implications for a field that has long struggled to find effective treatments. If confirmed in larger retatrutide clinical trials, retatrutide could join or complement other emerging therapies targeting MASH, such as FGF21 analogues or thyroid hormone receptor agonists, but with the added benefit of addressing obesity and diabetes simultaneously.

Importantly, the MASLD sub study provided a proof of principle that multi-agonist therapies can deliver clinically relevant changes in liver fat. It also reinforced the idea that obesity, diabetes and liver disease are interconnected metabolic conditions rather than isolated problems. By acting across multiple hormonal pathways, retatrutide may be uniquely positioned to influence all three domains at once.

In summary, the Phase 2a MASLD and MASH outcomes showed that retatrutide substantially reduces liver fat, improves several markers of liver health, and does so with a tolerability profile consistent with other incretin based drugs. While the histological data remain exploratory, the strong imaging results provide a compelling basis for moving forward with larger trials specifically designed for liver outcomes. As the global burden of MASLD and MASH continues to rise, therapies like retatrutide could play a key role in addressing a major unmet medical need.

Safety Profile Across Retatrutide Clinical Trials

Safety is always a central question in the development of new therapies, particularly those designed for long term use in large populations. With retatrutide, investigators have been able to gather safety data from Phase 1 first-in-human studies through multiple Phase 2 retatrutide clinical trials in obesity, type 2 diabetes and liver disease. The emerging profile is consistent with other incretin based drugs, though some features appear more pronounced due to the triple receptor mechanism. Understanding this profile is critical for anticipating how the drug might be tolerated in everyday practice if it is eventually approved.

The most common side effects across all studies have been gastrointestinal. Nausea, occasional vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation were frequently reported, especially during the early weeks of dose escalation. This is typical of GLP-1 receptor agonists, where gut hormone activity slows gastric emptying and alters appetite signalling. In most participants, symptoms were mild to moderate and tended to improve once a stable maintenance dose was reached. Strategies such as gradual dose titration and patient counselling on meal size were used to improve tolerability.

Discontinuation rates due to side effects were relatively low, though not negligible. In the Phase 2 obesity trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, around 6 to 8 percent of participants in higher dose groups stopped treatment due to adverse events. This was higher than placebo but similar to what is observed with semaglutide or Tirzepatide in comparable settings. The fact that the majority of patients remained on therapy through 48 weeks suggested that the side effects, while uncomfortable for some, were manageable for most with appropriate dose adjustment.

Laboratory monitoring in the retatrutide clinical trials has so far not revealed major safety concerns. Liver enzymes, kidney function tests and pancreatic markers were followed closely. No consistent patterns of hepatotoxicity or renal injury have been observed, which is encouraging given the populations studied. Pancreatitis, a rare but important concern with incretin based therapies, has not emerged as a significant signal in the retatrutide programme to date, though larger trials with longer follow up will be needed for definitive conclusions.

Cardiovascular safety has also been a focus. Blood pressure reductions were modest but favourable, and no increases in heart rate or arrhythmia events were reported. In fact, some early analyses suggest potential cardiovascular benefit, but this will only be confirmed in the dedicated Phase 3 outcomes trial that is part of the TRIUMPH programme

(ClinicalTrials.gov record). Until those data are available, the main message is that no red flags have been seen in preliminary monitoring.

Gallbladder events, such as gallstones or cholecystitis, were observed occasionally, as they have been with other incretin based drugs. The mechanism is thought to relate to rapid weight loss rather than a direct drug effect. These events were infrequent and generally managed with standard medical or surgical care. It remains an area that clinicians will need to monitor closely in future retatrutide clinical trials, particularly as patients may achieve very large and rapid weight reductions on therapy.

Another point of interest has been the drug’s impact on appetite and nutritional status. The profound reductions in energy intake raised questions about potential deficiencies or loss of lean body mass. So far, body composition analyses indicate that while fat mass accounts for the majority of weight lost, some lean tissue is also reduced. This is consistent with other weight loss interventions, and researchers are exploring whether exercise or protein supplementation can mitigate this effect. No safety concerns directly related to malnutrition have been reported in the Phase 2 programme.

In summary, the safety profile of retatrutide reflects a balance between predictable gastrointestinal symptoms, manageable discontinuation rates, and the absence of major new risks. The data so far, catalogued in journals such as the PubMed-indexed Phase 2 obesity trial and summarised by outlets including Healio Endocrinology, support continued development in larger populations. The upcoming Phase 3 retatrutide trials will be essential to confirm long term safety, assess rare events, and establish whether the metabolic benefits outweigh the tolerability challenges on a population scale.

Phase 3: TRIUMPH Program

After the strong Phase 2 results in obesity, diabetes and liver disease, Eli Lilly launched a global Phase 3 programme called TRIUMPH. These trials are designed to confirm the benefits of retatrutide in much larger and more diverse patient populations. Phase 3 trials also provide the kind of data regulators require for approval, including long term safety monitoring and outcomes that go beyond simple weight loss. Recruitment began in 2023 and the programme spans several therapeutic areas, reflecting the broad potential of the triple-agonist approach.

The backbone of the programme is TRIUMPH-1 and TRIUMPH-2, which are large scale obesity studies involving thousands of participants across multiple countries. According to the ClinicalTrials.gov listing, TRIUMPH-1 is focused on adults with obesity without diabetes, while TRIUMPH-2 includes those with type 2 diabetes. Both trials will run for more than a year and measure primary outcomes of weight reduction alongside secondary endpoints such as HbA1c, blood pressure and quality of life. The design mirrors the Phase 2 work but at a much larger scale, providing definitive efficacy data.

TRIUMPH-3 is dedicated to people with sleep apnoea, a condition that is often linked with excess weight. Previous studies have shown that weight reduction can improve or even resolve sleep disordered breathing. By testing retatrutide in this group, Lilly aims to see if the drug can provide benefits that extend beyond metabolic measures and into respiratory health. This study is one of the

first of its kind, and details are available through its trial registry entry.

A further pillar is the cardiovascular outcomes trial, TRIUMPH-Outcomes, which will follow tens of thousands of patients over several years. This trial will assess whether retatrutide reduces the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events such as heart attack, stroke or cardiovascular death. For regulatory agencies, such as the FDA and EMA, cardiovascular safety data are a requirement for new metabolic therapies, and many incretin based drugs have also shown cardiovascular benefit. The outcomes study will therefore be critical not only to establish safety but also to test whether the metabolic improvements seen in Phase 2 translate into reduced event rates in the real world.

Lilly has also initiated exploratory studies in other metabolic conditions, including MASLD and MASH, building on the encouraging Phase 2a sub study published in Nature Medicine. While these are not formally labelled under TRIUMPH, they run in parallel and add to the broader development package. By diversifying trial populations, Lilly hopes to position retatrutide as a multi use therapy across obesity, diabetes, liver disease and related complications.

External commentary has noted the ambitious scale of the TRIUMPH programme. Publications like Healio Endocrinology have highlighted how the company is moving aggressively to compete in the incretin market, where Semaglutide and Tirzepatide already hold strong positions. The differentiation strategy is clear: by demonstrating superior weight loss and added benefits in areas like liver health and sleep apnoea, retatrutide could carve out a role that goes beyond existing products.

In summary, the TRIUMPH programme represents the decisive stage in Retatrutide’s clinical development. With multiple large retatrutide clinical trials across obesity, diabetes, sleep apnoea and cardiovascular outcomes, it is designed to answer both efficacy and safety questions on a global scale. Results are expected later this decade, and if they confirm the Phase 2 promise, retatrutide could emerge

as one of the most important new therapies in metabolic medicine. Until then, the drug remains an experimental compound, and all information must be interpreted within a research context.

Trial Timeline & Milestones

The clinical development of retatrutide has moved at a rapid pace compared with many other metabolic therapies. The journey began in 2021 with the initiation of first-in-human Phase 1 studies. These early dose-escalation trials focused on safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics, confirming that the compound could be delivered safely in humans and that once-weekly dosing was feasible. Early findings, shared through conference abstracts such as those presented at the American Diabetes Association meeting (scientific abstract), provided the first indications that the triple-agonist approach was biologically active.

In 2023 the programme reached its first major milestone with the publication of the Phase 2 obesity trial in the New England Journal of Medicine. This study demonstrated average weight losses exceeding 24 percent at the highest doses over 48 weeks. The results, also indexed on PubMed, drew global attention as few non-surgical interventions had achieved similar outcomes. Around the same time, Lilly released the findings of the Phase 2 type 2 diabetes trial in The Lancet, showing that retatrutide could significantly reduce HbA1c while delivering weight reduction in a more complex patient group.

A further milestone came in 2024 with the release of data from the liver sub study, which was published in Nature Medicine. This analysis demonstrated dramatic reductions in liver fat among participants with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, confirming the potential for retatrutide to impact conditions beyond obesity and diabetes. The findings were logged on PubMed and widely discussed in hepatology circles, where new treatment options are urgently needed.

Building on these successes, Lilly formally launched the Phase 3 TRIUMPH programme in late 2023. The first studies to begin recruitment were TRIUMPH-1 and TRIUMPH-2, which focus on obesity in people with and without type 2 diabetes. Registry records such as NCT05774445 outline the trial design, including large sample sizes and a follow-up period exceeding one year. Additional trials soon followed, including TRIUMPH-3 in sleep apnoea and TRIUMPH-Outcomes, a cardiovascular outcomes study that will enrol tens of thousands of participants worldwide. These retatrutide clinical trials are designed to provide the scale and duration of evidence required for regulatory submissions.

The projected timeline sees primary readouts from TRIUMPH obesity trials expected around the middle of the decade, with cardiovascular outcomes data likely to come later, closer to 2028 or 2029. If these milestones are reached successfully, Lilly may file for regulatory approval before the end of the decade, positioning retatrutide as a competitor to established GLP-1 and dual agonist drugs. Commentaries in outlets like Healio Endocrinology have noted the aggressive pace of development and the ambition to establish leadership in the next generation of metabolic therapies.

In summary, the development of retatrutide has followed a clear sequence of milestones: Phase 1 proof of safety in 2021, breakthrough Phase 2 obesity and diabetes results in 2023, liver sub study confirmation in 2024, and the launch of the expansive Phase 3 TRIUMPH programme that is now underway. The timeline illustrates both the scientific promise of the compound and the urgency driving its progression. While much depends on the outcome of ongoing studies, the milestones already achieved have positioned retatrutide as one of the most closely watched candidates in global metabolic research.

Order Retatrutide Online

Available in 10mg vials. Select your pack size and checkout securely below.

-

Reta 10mg 3 Vials

£195.00Independently verified COA. UK stock, worldwide delivery. For lab use only.

FAQ

- What is retatrutide?

Retatrutide is an investigational drug being studied as a triple-agonist that activates GLP-1, GIP and glucagon receptors. It is being tested for obesity, type 2 diabetes and liver disease, but it has not yet been approved for clinical use. - Why is retatrutide different from existing weight loss drugs?

Unlike single-pathway drugs such as semaglutide, retatrutide combines three hormone targets in one therapy. This design may deliver greater weight reduction and broader metabolic benefits, though longer trials are needed to confirm. - When did clinical trials for retatrutide begin?

Phase 1 trials began in 2021, establishing safety and dosing schedules. Phase 2 trials in obesity and type 2 diabetes followed in 2023, with a liver sub study published in 2024. Large-scale Phase 3 studies are now underway globally. - How much weight loss was reported in obesity trials?

In the Phase 2 obesity trial, participants on the highest doses lost more than 24 percent of their baseline weight over 48 weeks. Lower doses also delivered double-digit reductions, showing a strong dose–response effect. - What were the results in people with type 2 diabetes?

The Phase 2 diabetes trial showed HbA1c reductions of up to two percentage points and weight loss of 10–15 percent. Fasting glucose and insulin sensitivity improved, highlighting potential dual benefits for glucose and weight management. - What impact does retatrutide have on liver disease?

A sub study in Nature Medicine reported substantial decreases in liver fat in patients with MASLD and diabetes. Some participants achieved normal liver fat levels, and biomarkers linked to inflammation and fibrosis risk improved. - What are the most common side effects?

Gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, diarrhoea, constipation and occasional vomiting are most frequently reported. These usually occur during dose escalation and improve over time, though a minority of patients discontinue therapy. - Are there serious safety concerns?

So far, no major new safety concerns have emerged. Pancreatitis and gallbladder issues are monitored but have remained infrequent. Cardiovascular safety is under investigation in ongoing Phase 3 trials. - How is retatrutide given?

Trials use once-weekly subcutaneous injections, similar to other incretin-based drugs. The schedule was chosen based on its half-life, which allows sustained activity across a seven-day cycle. - How does dose escalation work?

Participants start at low doses that gradually increase every few weeks until a maintenance level is reached. This helps minimise gastrointestinal side effects and improves overall tolerability. - What is the TRIUMPH programme?

TRIUMPH is the Phase 3 programme testing retatrutide in obesity, type 2 diabetes, sleep apnoea and cardiovascular outcomes. These large global studies are designed to confirm efficacy and long-term safety. - Will retatrutide be tested for cardiovascular outcomes?

Yes. The TRIUMPH-Outcomes trial is specifically designed to assess whether retatrutide reduces major cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke and cardiovascular death. - What effects does retatrutide have on appetite?

Patients report reduced hunger and earlier satiety, consistent with GLP-1 activity. This appetite suppression is believed to be a major driver of the weight loss seen in trials. - Does retatrutide affect lean body mass?

Body composition analyses suggest most of the weight loss comes from fat mass, though some lean mass is also reduced. This is common with all weight loss methods, and researchers are studying ways to preserve lean tissue. - How does retatrutide compare with Tirzepatide?

Direct comparisons are not yet available, but Retatrutide’s Phase 2 results showed greater weight loss percentages over similar time frames. Larger head-to-head studies will be needed for confirmation. - What was learned from Phase 1 studies?

Phase 1 confirmed that retatrutide could be dosed once weekly and was generally well tolerated. Early biomarker changes showed activation of all three receptors, supporting advancement into Phase 2. - What secondary outcomes were seen in obesity trials?

Improvements were recorded in waist circumference, blood pressure, cholesterol levels and quality-of-life measures. These outcomes suggest metabolic benefits extend beyond weight reduction alone. - How long did the Phase 2 studies run?

The obesity study lasted 48 weeks, while the diabetes trial ran for 36 weeks. These durations provided enough time to evaluate both early responses and sustained effects across nearly a full year. - What is MASLD and MASH?

MASLD refers to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, formerly called NAFLD. MASH is the more advanced stage, with inflammation and cell injury, previously known as NASH. - What happened in the MASLD sub study?

Patients treated with retatrutide showed liver fat reductions of more than 70 percent from baseline in some cases. Several reached normal levels, and non-invasive fibrosis scores also improved compared with placebo. - Are there concerns about gallbladder problems?

Gallstones and related issues were observed occasionally, similar to other incretin drugs. Rapid weight loss is thought to be the main factor, and these events were managed with standard care. - When are Phase 3 results expected?

Initial readouts from the obesity and diabetes studies are anticipated around the middle of the decade. Cardiovascular outcomes data will take longer, with results expected closer to 2028 or 2029. - Could retatrutide be used for sleep apnoea?

Yes. A dedicated Phase 3 trial is testing whether weight loss with retatrutide improves obstructive sleep apnoea, a condition strongly linked to obesity. Results are pending. - Is retatrutide available to the public?

No. Retatrutide is only accessible through controlled clinical trials. It has not been approved for prescription use in any country. - What happens next in development?

The TRIUMPH programme will provide definitive data on efficacy, safety and long-term outcomes. If positive, Lilly may seek regulatory approval before the end of the decade, but approval will depend on the results.

Compare Clinical Trial Data

Compounds in Similar Trial Phases

- Orforglipron trials – Oral GLP-1 in Phase 3

- Cagrisema trials – Amylin combination in development

- Survodutide trials – Dual agonist in trials

Approved Comparators

- Semaglutide – Completed trials

- Tirzepatide – Recently approved

Explore our Trial Twin tool | View all 48 comparisons